What Seems to be the Problem?

Can we make any progress on transport while we don't recognise there's a problem to be solved and can't recognise solutions?

When you think about it, medicine is really unpleasant.

Ibuprofen is available on every high street, yet given the list of common side effects it's hard to imagine anybody would swallow these pills without a good reason. And ibuprofen is one of the more benign treatments out there. How many people would spontaneously volunteer to be sliced open by a surgeon's scalpel, or poisoned by chemotherapy? These are brutal treatments that I suspect hold little appeal to most people.

And yet every day, large numbers of people voluntarily put themselves forwards to be cut, or poisoned, by these procedures. Clearly, people will put up with even deeply unpleasant experiences when they believe it will solve a problem.

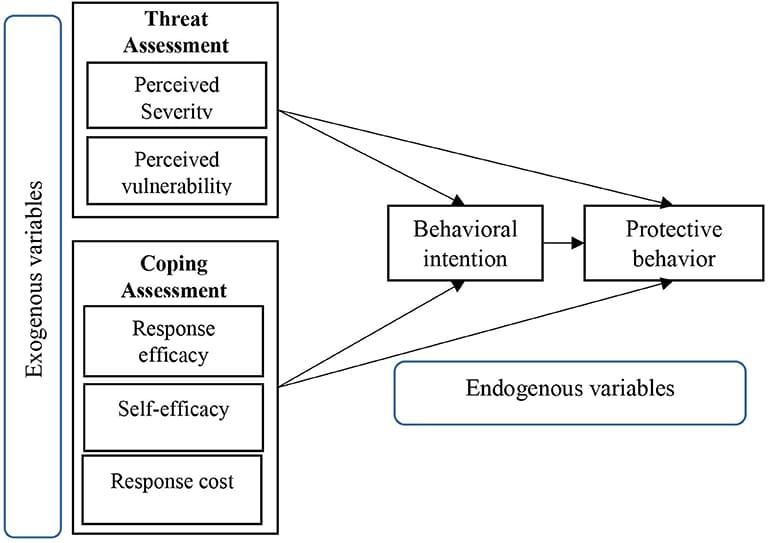

Health Psychologists have said a lot about this sort of thing over the years. For example, Protection Motivation Theory suggests that people are more likely to take action to improve their health – even if this involves being knocked unconscious and sliced open – when a handful of necessary conditions are in place. I'm simplifying slightly here, but basically the theory says that people are likely to engage with a health treatment when (1) they believe there is a problem to be solved, (2) they believe it is serious, and (3) they believe that this intervention will solve the problem. Only if you believe you have a tumour, and you believe it's harmful, and you believe the surgery will get rid of it, are you likely to welcome the surgery. Just one or two of those beliefs probably won't be enough. Try it: imagine any two of the three. Imagine you believe that tumours can be harmful and that surgery is great for removing them... but that you don't have a tumour. How's that scalpel looking?

I think about this sort of thing a lot when I think about transport. It's hard not to speculate that some similar process must underpin our collective and individual failures to address the many many many many problems with our current transport system. Either we fail to recognise there is a problem with today's car-dependent societies, or we fail to believe it is serious, or we fail to believe that the solutions that are being put forward will solve things.

It's very likely all three of these, of course.

Presumably part of the issue is that many people see such a tiny part of the picture that they don't really understand what the problem is. Perhaps, like a depressingly large proportion of the people who live around me here in Swansea, they hop into the car for practically every trip, of every length, and so see the problems of car-dependency only as they appear from behind the steering wheel: the need to pay for fuel (as if they haven't been drastically cushioned in this regard), the difficulty finding places to store their car that don't already have cars all over them, or the nuisance of having their trips prolonged because the road is jammed with other people driving their cars – usually for a short distance, all by themselves. From this perspective, it is no wonder people shun the cure – the solutions that urbanists and sustainable transport are offering must appear totally unrelated to the problems that these people are perceiving. It must feel like calling a plumber to look at your leaky toilet only for them to turn up and offer you a salad. Very worthy perhaps, but it's not clear how it fixes my leaky toilet.

It is this appraisal process, where people (mis)judge the transport solutions on offer, that I want to explore slightly further here. And perhaps the most logical way to explore people's (mis)perceptions of response efficacy is by thinking about dog shows.

The Dog Show Problem

John Finnemore once wrote a brilliant comedy sketch about dog shows, in which... well, go and listen to that link; it's less than 3 minutes and I think you'll find it funny. But basically, the joke is that the "best dog" in a dog show is not the fastest dog, or the most agile dog, or the cleverest dog... but rather the dog that looks most similar to the picture of a dog that the dog-show organisers have drawn on a piece of paper.

I suspect, thanks to motonormativity, something very similar is happening with transport. Speculatively, I wonder if we've reached a point where, after 100 years of car-first thinking and planning, every mode of transport is automatically judged by how closely it resembles the private car.

Take the bus? No, for it does not resemble my car. In my car I travel alone and I leave at the exact moment of my choosing. The bus does not do these things, and therefore it is not transport.

Ride a bike? No, for it does not resemble my car. My car has a roof. A bicycle does not have a roof, and therefore it is not transport.

Drive an electric car? No, for it do— Actually, okay, yes... but only if it looks and sounds exactly like my petrol car, down to having the same oversized body, the exact same abundance of empty seats, and even the same level of noise pollution that I have grown accustomed to – even if that noise must be pumped out through a speaker. For as we all know, if it is quiet, it does not resemble my car and therefore it is not transport.

The more serious way of framing this argument is that one way in which motonormativity manifests itself is through our sharing a flawed mental model, or schema, of what transport is (and isn't) and that this is messing up our judgements. This is just a hypothesis, but my goodness it would certainly explain a lot – and might suggest that if we want to make a change, it will not be enough to provide alternatives to the private car that meet the same goals, or even exceed them, if they are automatically going to be judged by that same old two-tonne five-seat yardstick. It all points again to the idea that we're not getting out of this, no matter how good an alternative we offer to the car, unless we also make jumping into that car a lot more difficult.

But to try to finish on an optimistic note: if the supposition I've sketched out here is correct, we should only need to make driving more of a challenge for long enough until our shared mental models of what transport is and isn't – those oily Platonic ideals that pollute our collective minds – have finally faded away.

A generation or two ought to do it.

New research

There's a growing body of research on how everyday language – especially from the media – might reflect, and help perpetuate, motonormativity. News headlines like "Emergency crews called as car crashes into building" (one of literally dozens of published examples I could have chosen from just the past few days) unconsciously and insidiously remove all the agency from the driver. Texts like these daily send the message that cars crashing into stuff is just a thing that happens – and they thereby imply that there's nothing we can do about it.

A new study has just appeared that builds on past work from Tara Goddard and colleagues, but this time in the German context. Like Tara's study, the new German work shows how the choice of language used to describe incidents on the road subtly, and probably unconsciously, shifts the blame and responsibility for the harms of motoring away from the drivers and from the designers and legislators of the road system, making the toll of death and injury feel inevitable and unchangeable. This is all the more reason we need responsible media to follow reporting guidelines like Laura Laker's, and take care not to reinforce the belief that road violence is normal and inevitable.

Bye

Thanks for reading. This is the first of these newsletters, so I'm sure they'll evolve over time. In the meantime, keep fighting the good fight. Do share this with your friends/enemies and encourage them to subscribe. Or, y'know, just break into their email accounts and sign them up.