Let's do the maths

Thinking about traffic planning with a slice of pi

You perhaps remember from your time at school the formula to calculate the area of a circle. It's pi, multiplied by the radius of the circle squared. This is handy, because a circle very roughly covers the area a person can reach when they travel for a certain number of minutes from their home. A circle therefore provides a simple but useful model we can use to think about the impacts of travel policies.

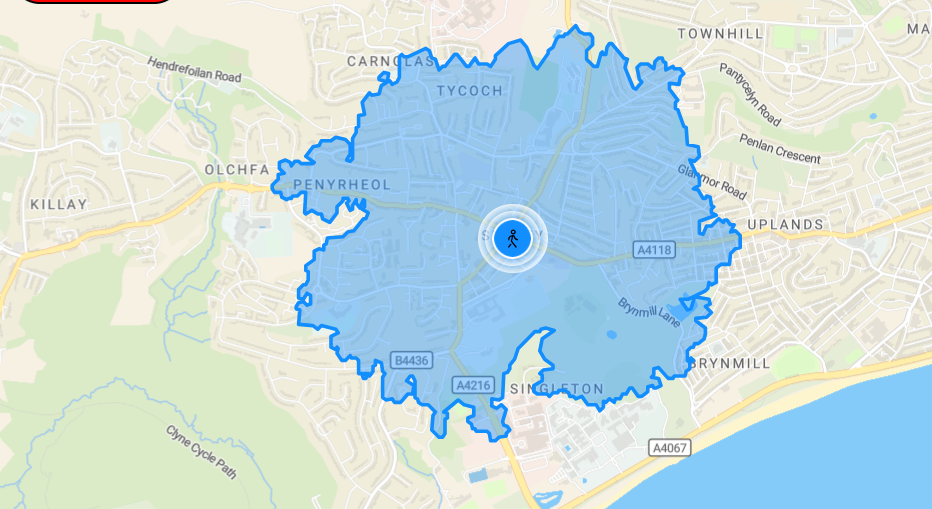

(In reality, of course, unless you live in a desert, the area you can reach in a given period of time is not exactly a circle. If you want to explore the true isochrone map for places you know, there's a handy website for this. For example, this picture shows the places you can reach in 15 minutes' walk from Sketty in Swansea - it's not quite a circle, but a circle is close enough to be a rough model of the zone.)

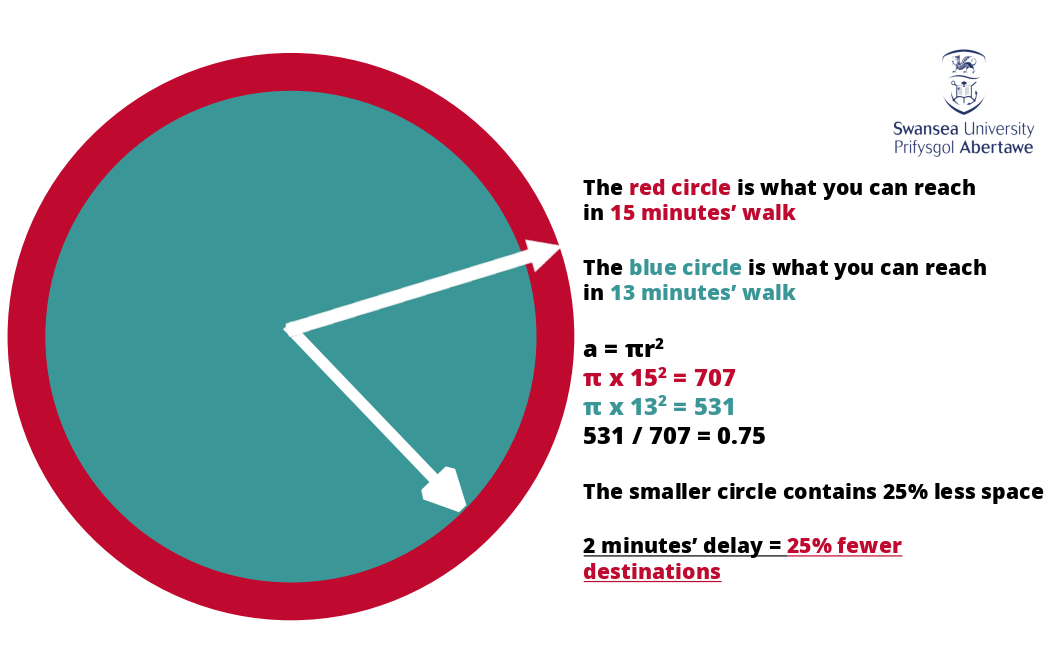

I've been thinking about these circles for a while now, and so I used a recent invitation from Cycling UK to speak at Stormont in Belfast as a chance to do the maths. Here's a slide I showed at that event:

This very simple modelling exercise shows that two minutes' delay to a pedestrian's journey – that is, a delay of 13% of the trip length – reduces by 25% the number of places they can reach in 15 minutes. That's 25% less access to shops, work, education, social and leisure opportunities. Yet in a motonormative society, where the default at every crossing point is for pedestrians to stop and wait for motorists rather than the other way around, it is not unusual for a pedestrian to have two minutes taken from a 15-minute walk, and thus to have a quarter of potential destinations placed out of their convenient reach.

Living Streets have been characteristically good at flagging the issue of pedestrian-crossing wait times. Their Edinburgh branch, for example, went out and did some counting, finding wait times up to 95 seconds for mid-block crossings and up to 285 seconds (that's nearly five minutes) for signalled traffic intersections. (To save you doing the maths, a wait of 285 seconds would reduce a pedestrian's 15-minute accessibility zone by 53%.)

I originally wrote a big rant here about the traffic and street engineering professions, but it was just too angry for me to post. My hope is that the numbers coming out of these simple models will be enough to make the point: we have to look again at what the streets in our towns and cities are for, because by systematically valuing drivers' time ahead of non-drivers' time, and by placing the burden of waiting onto the non-driver by default, we are surely encouraging more people into cars for more trips. The evidence is pretty clear that if we want a healthier, cleaner society, we have to do the opposite of that.

The formal line

Perhaps surprisingly, given the car-first streets that are all around us, the UK Department for Transport guidance on crossings actually contains some good advice in Section 11.1. This reminds engineers that while a driver might not enjoy waiting at a junction they, unlike the pedestrian, are at least definitely warm and dry; it also tells engineers that footbridges and underpasses should generally be avoided, which seems like good advice. But for all those fine words, the bulk of that document fundamentally still describes a car-first road system. I'm reminded of a recent conversation with some traffic engineers in which they justified pedestrian wait times at crossings by saying these allow pedestrians to 'stack up', so that several can cross the road at the same time when they are released, thus minimising their impact on drivers' journey times. It's curious to see the dreadful spatial efficiency of motor vehicles being taken as something that has to be accommodated, while the efficiency of walkers, wheelers and cyclists is used as a stick to beat them with.

These issues are only going to get more pressing. My colleagues and I just published a new paper suggesting that proper separation between travel modes is likely essential if we want people to walk, wheel or cycle more (give it a read: it's interesting). If we want to put different travel modes into separate spaces, this means their routes will need to cross one another, and this will mean making choices about who gives way to whom. In doing this, we can choose to lean towards a principle like 'steam gives way to sail' or we can choose a principle like might is right, but I don't think we can have it both ways. Choices have to be made and, critically, leaving the status quo untouched is also a choice – one that sends a powerful message about how, for all governments' fine words and glib declarations of climate emergency, our streets are strongly sending us a message that we should travel any way but walking, wheeling and cycling. You only have to look at how 58% of UK car trips are below 5 miles to see that people are hearing this message loud and clear.