But who speaks for the dead?

Break out the ouija boards and activate the ghost of Doris Stokes. We're reaching back beyond the grave to solve today's transport and environmental crises.

Here in Wales, one of the more interesting developments in recent years has been the Welsh parliament, the Sennedd, passing the Well-Being of Future Generations Act.

(I presume they're already regretting that hyphen in the title. If there's one thing we should have learned by now it's that hyphens tend to dissolve over time. Who today writes 'e-mail', 'chick-pea' or 'lava-tory'? Although, to be fair, I did just make that last one up.)

Thanks to the Act, Wales now has a Future Generations Commissioner whose role is "to support and challenge Wales to make decisions in the best interests of people who aren’t born yet".

I'm sure there's a discussion to be had about how much impact the Act is actually having on the Welsh Government's actions, but what I'm interested in here is the intent and the philosophy of the Act, and how striking it is that this approach of trying to include potential opinions from people who do not currently exist only extends forwards through time.

Can future transport learn from the past?

Anyone who understands the issues with today's transport system will know that enabling more healthy active travel would definitely be in the interests of future generations. This got me thinking: while Wales has appointed somebody to speak for these people – and while I hope the Commissioner is already feeding into in planning decisions around active travel and public transport – who is there to represent the people who legitimately have an interest in these topics but who can no longer represent themselves? In other words, who speaks for the dead?

When a local authority proposes a segregated cycle lane, and a few locals loudly protest and demand the streets remain dangerous to people on bikes, who represents all the cyclists who have been killed because they were not given safe places to ride? If they could speak, I'm confident I know what they would say about the proposals. But we don't seem to care what their views would have been, and we consult in a way that disproportionately favours one side of the discussion. We have a form of survivorship bias where the people who most get to opine on the status quo are, by definition, those for whom it demonstrably works; many of those for whom the status quo did not work have been systematically, and brutally, excluded.

When an authority wants to remove motor vehicles from an area to reduce air pollution, what do we think the hundreds of thousands of people whose lives have already been cut short by that air pollution would say, if somehow the consultation could include them? They very clearly had an investment in the subject, after all. Where is the Commissioner tasked with representing what they would be likely to say if they hadn't been excluded from the consultation by the very air pollution under discussion?

Speaking for the potential future

As well as the voices of the excluded dead, I wonder if we should also try to consider another set of future people. I'm not thinking as far ahead as future generations here; we really only need to look as far ahead as next year.

We know from cities like Paris that if well-designed (welldesigned?) safe spaces are provided so that people can move around without cars, many people will start to do it. People aren't born as cyclists, drivers or bus-riders; they respond to their environments and adopt whatever modes feel easy, normal and safe. This means that in any car-dependent locale, there are thousands of potential cyclists, potential walkers and potential bus-users. They don't know there is a possible future in which a rethink of the streets means that they will become walkers, cyclists or bus-riders and so, although for many of them that is the case, they are today unlikely to speak up for walking, cycling or buses. So why do we not include, in every consultation about developments to the public realm, a commissioner who speaks on behalf of all the people who would change their minds if the development went ahead, as the evidence tells us they would? We have enough data to estimate how large this voice should be. Let's conservatively say 20% of people would start to cycle in a place designed to make this feel easy and safe. In that case, should a town of 20,000 people appoint an agent who puts 4000 extra submissions into the consultation, all of them in support of the development?

I can anticipate the concerns with this, and in an age of populism I'm nervous of even hinting at anything that looks like fiddling with a voting system. But, critically, public realm consultations are not referendums. They ought to be about giving decisionmakers an idea of the range of views that exist within the people who might be affected by the proposals; what I am thinking about here is merely intended as a way of making that process much more comprehensive, and making sure the process includes – in a defensible way – potential voices and perspectives that are currently systematically excluded because of how consultation happens at a very specific and limited single point in time... too soon for some to have their say and, tragically, much too late for others.

Back from the north

Every 26 years I like to head over to Belfast to visit Stormont. Well, more technically I went there for a conference when I was a student in 1999 and I went back there this week. Are human beings too susceptible to spotting patterns in meaningless data? Who knows, but I'm just on booking.com locking down a hotel for 2051 and I can't find the option to reserve a parking space for my flying car.

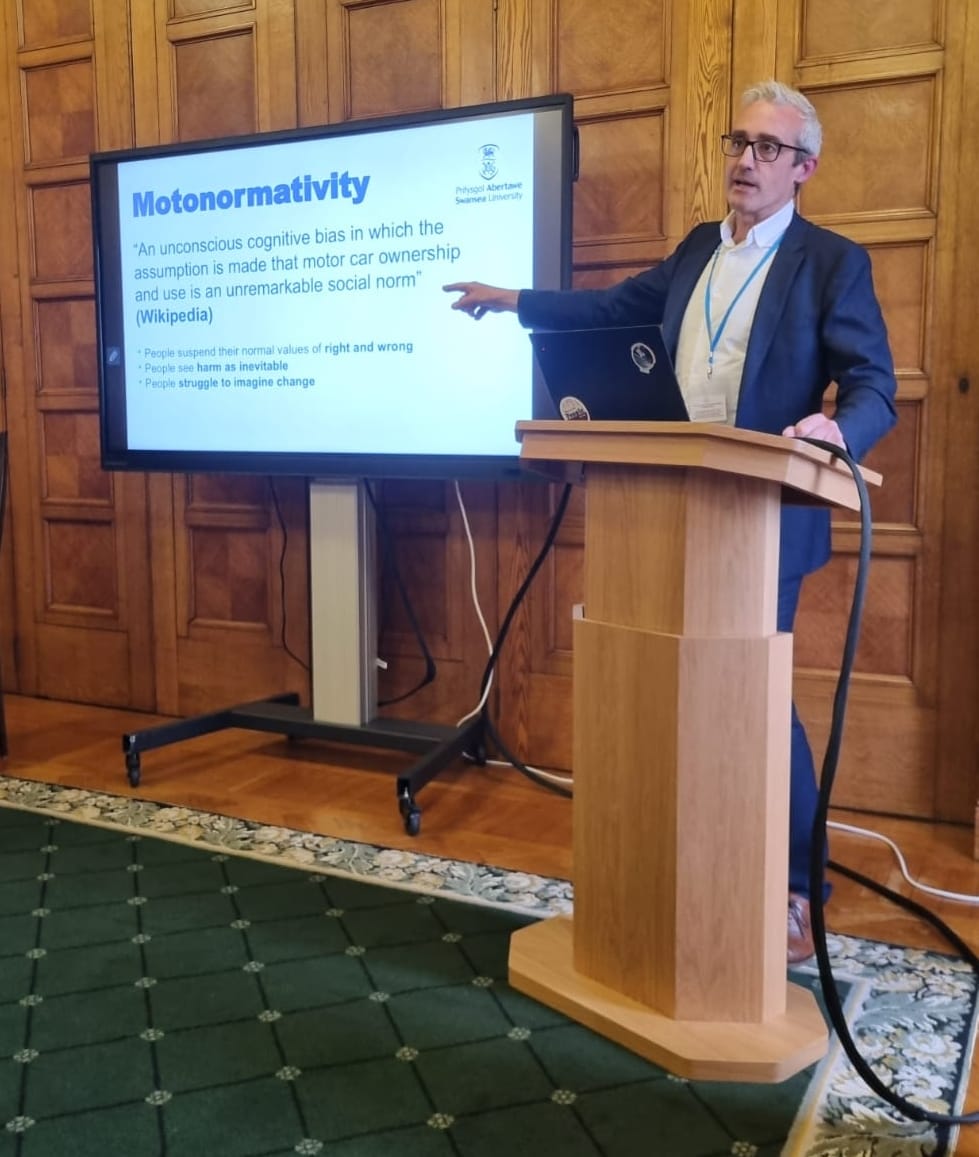

More seriously, this week was a chance to talk to a range of practitioners, students and even one or two politicians about the problems of motonormativity. You can never know when these things will make a lasting difference, but I do like to try.

Very big thanks to Cycling UK and Queen's University Belfast for inviting me over.

Shameless self-promotion! I don't just wang on about bikes professionally; I've also been known to ride them. After breaking the Guinness World Record for the fastest bicycle ride across Europe a few years ago, I wrote a "jaw-dropping account" (road.cc) of suddenly transitioning, in my 40s, from slothful layabout to world-class ultra-endurance athlete, and the various life-lessons I learned along the way. The perfect Christmas present? Well, that's very kind of you to say so.

Right, that's it for another newsletter. Thanks for reading. Love to you all.